Manitoba 분류

우리가 먹는 위니펙 수도물은 어디서 올까?

작성자 정보

- 작성일

컨텐츠 정보

- 15,807 조회

- 목록

본문

위니펙시에서 공급하는 수도물은 온타리오(Ontario)주와 인접한 Shoal Lake 에서 가져 온다는 위니펙 프리 프레스(Winnipeg Free Press) 신문기사가 있어서 관련 기사와 동영상을 가져왔습니다.

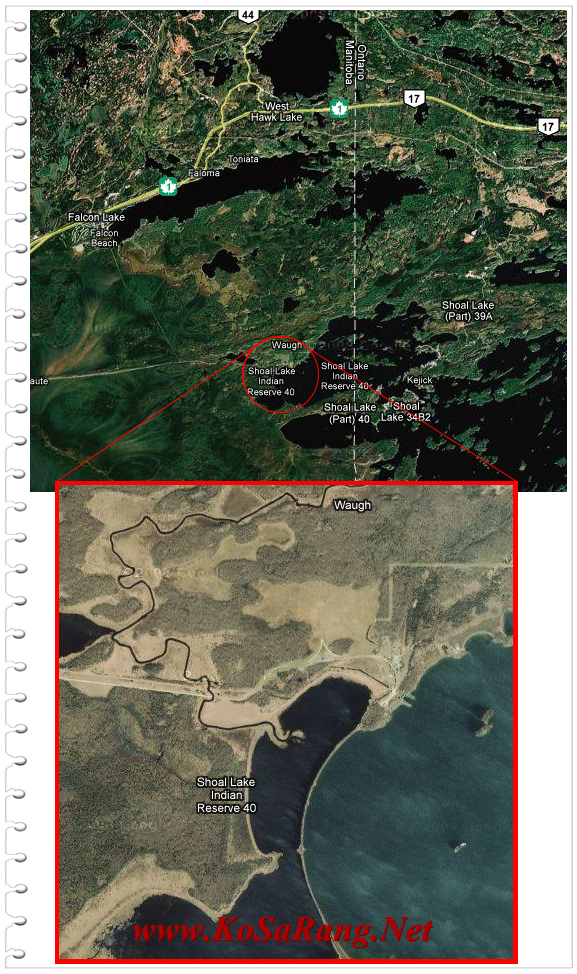

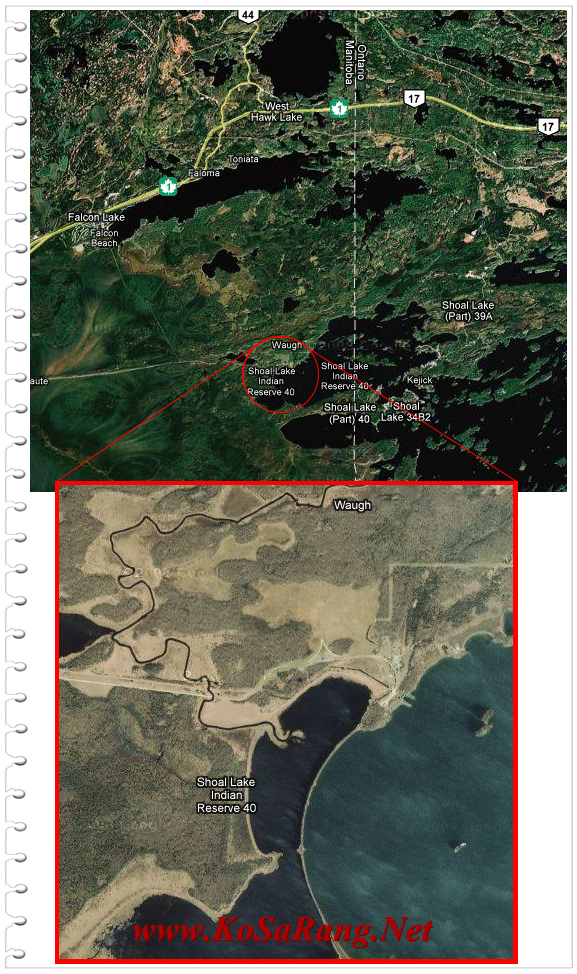

그리고 좀 더 자세히 알기 위하여 구글맵(http://maps.google.ca)에서 Shoal Lake 를 찾아봤습니다. Shoal Lake는 Ontario주 Lake of Woods 와 인접해 있는 호수로 한국분들도 많이 놀러가는 Falcon Lake 남쪽에 있더군요.

위니펙시 수도는 90년전에 위니펙시로부터 156 km 떨어진 Shoal Lake 에서 위니펙시까지 두개의 수로를 건설하여 시민들에게 수도물을 공급하면서 시작했습니다. 그것에 얽힌 얘기를 간단하게 요약을 합니다.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

20세기초에 위니펙은 캐나다 횡단철도를 따라 많은 사람들이 오면서 도시가 급격히 커지기 시작했습니다. 그리고 먹는 물을 공급하기 위하여 개인회사가 아시니보인강변에 펌프를 설치하고 물을 공급하기 시작했습니다. 그 당시 물은 무척 불결해서 50명중 한명은 장티푸스, 콜레라, 또는 물과 관련된 병으로 죽었다고 합니다. 이에 1906년에 위니펙시는 지하수 우물(artesian wells)로 부터 물을 공급하기 시작하였으나 수요에 공급이 크게 못미쳤다고 합니다.

그래서 시는 깨끗한 물을 공급할 대책을 의논하기 시작했고, 시북쪽에 큰 우물을 여러개 파서 물을 공급하는 안, 위니펙강(Winnipeg River)에서 물을 끌어 오는 안, Shoal Lake 에서 물을 끌고 오는 안 등 3개안이 경합을 벌였다고 합니다. 당시 미국의 수도 건설 자문을 맡은 Charles Schlicter 가 Shoal Lake 안이 1912년 당시 돈으로 수로를 건설하는데 $13.5 million 이 들 것이라는 발표가 난 후 엄청 시끄러웠다고 합니다. 1913년 Shoal Lake 부근에 살던 시위원 Thomas Deacon 이 지지하는 Shoal Lake 안으로 결정이 되었고, 그 해 Thomas Deacon 이 위니펙 시장으로 당선되었고, 그 다음 시장으로 Deacon 의 뒤를 이어 Richard Waugh 이 선출되었습니다.

Charles Schlicter 발표한 Shoal Lake 안 수로 건설비는 당시 세계에서 인구가 빠르게 증가하는 도시중 하나로 미래의 증가할 인구수까지 감안하여 작성된 것이었습니다. 그는 그 증가하는 인구에게 임시적인 방법이 아닌 지속적으로 물을 공급할 수 있는 수로 용량으로 계산한 것으로 그의 계산은 일부가 잘못된 것이었습니다. 왜냐하면 1912년을 기점으로 위니펙시 인구가 증가하지 않고 정체했기때문이었습니다. 하지만 결과적으로 위니펙시는 굉장한 상수도 시스템을 갖게 되었습니다.

위니펙시에서 Shoal Lake 까지는156Km 거리로 고저차가 92 m 에 이릅니다. 1912년부터 1915년까지 위니펙시 외곽에서 Shoal Lake 까지 건설물자와 노동자를 운반하기 위하여 먼저 1,200명의 지역 및 이민 노동자가 투입되어 철도(The Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway)를 건설했습니다. 그리고 그들은 철도길 옆에 콘크리트로 말발굽모양의 수로를 건설하는데 다시 투입이 되었습니다.

1919년 수로가 완공되었을 때, 총공사비는 $17 million 로 늘어나 있었습니다. 2009년까지 물가인상율을 감안하면 $210 million 에 달하는 금액입니다. 하지만 오늘날 이 정도 크기의 공사를 실제로 한다면, 지난 90년동안의 노동인금과 건설자재값의 상승을 감안하면 아마도 쉽게 $1 billion 는 넘을 것입니다.

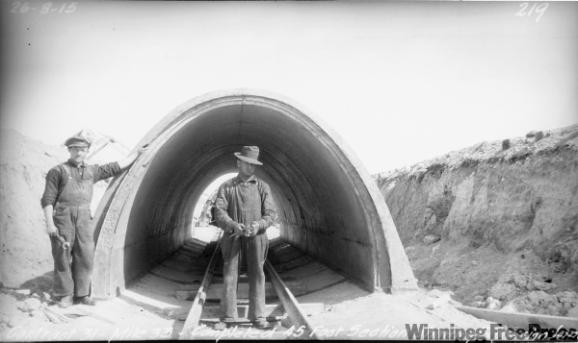

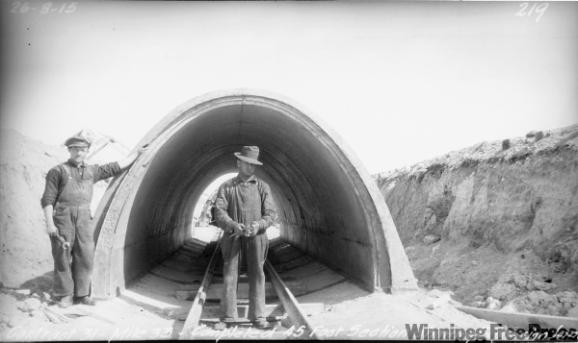

사진설명 : Shoal Lake Aqueduct under construction c1917

출처 : Winnipeg Free Press

처음 Shoal Lake 안을 지지했던 시장 Thomas Deacon 의 이름은 위니펙시 동쪽에 있는 정수장 the Deacon Reservoir 의 이름으로 사용되었고, 다음 시장 Richard Waugh 는 Shoal Lake 부근 수로입구의 지명으로 사용되었습니다.

구글맵에서 찾아 본 Deacon Reservoir 정수장

한두사람의 선견지명에 의해 수많은 사람들이 혜택 받는 것을 보면 정말 지도자를 잘 뽑아야 한다는 것을 알 수가 있습니다. 90년전에 지은 두개의 수로가 위니펙의 약 70만명 시민에게 아직까지 깨끗한 물을 정상적으로 공급한다는 것이 놀랍습니다.

다음은 위니펙 프리 프레스에서 찍은 동영상입니다.

좀 더 자세한 역사를 알고 싶은 분들을 위하여 위니펙 프리 프레스(Winnipeg Free Press) 기사를 덧붙입니다. 참고하세요.

Our drinking water was so filthy, as many as one in 50 Winnipeggers died of typhoid, cholera and other water-borne diseases, making the Manitoba capital one of the least safe cities on the planet to take a swig.

In 1906, the city started pumping water out of artesian wells. But the supply was too small to put out major fires.

So the city began to mull its options for a permanent and plentiful source of clean drinking water. City councillors wound up with three contenders: A larger series of wells north of the city, the Winnipeg River and Shoal Lake.

The debate over the choice was boisterous and divisive, especially after an American water consultant named Charles Schlicter pegged the price of the Shoal Lake option at $13.5 million, in 1912 dollars.

Schlicter based his decision on the fact Winnipeg was one of the fastest growing cities in the world at the time. Based on future population projections, it would need a substantial water supply.

"Winnipeg has entered into a class of world cities. It cannot afford to be committed to a temporary solution and it should not postpone the inevitable," wrote Schlicter, according to Siamandas.

Then-councillor Thomas Deacon, who had lived near Shoal Lake, pushed for the Indian Bay option. He won the decision in 1913 and was elected mayor later that year, succeeding Richard Waugh.

As it turned out, Schlicter was partly wrong: Winnipeg's runaway growth halted in 1912. But the decision to build the aqueduct was fortuitous in the sense it has wildly exceeded its expectation, in terms of both capacity and longevity.

Deacon is now immortalized by the Deacon Reservoir just east of Winnipeg. Waugh received the secondary honour of lending his name to the unincorporated community at the intake site.

But before construction could begin, the city had to build a railway all the way to the intake site to transport all the manpower, machinery and materials to build the aqueduct. Concrete and steel could not be schlepped on foot or horseback over the prairie, forest and bog that separated Winnipeg from Indian Bay.

The Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway was laid down between 1913 and 1915 by 1,200 local and migrant workers. They then went to work on the task of building the aqueduct itself, which features a flat bottom of steel-reinforced concrete with a horseshoe-shaped concrete arch over top, which derives its strength from its own weight.

Every mile along the aqueduct, the top of the arch was reinforced with steel to allow for future road crossings. Rural Manitoba has a network of roads spaced one mile apart, and the designers wanted to make sure motor vehicles would not destroy the aqueduct.

The circumference of the aqueduct varied, depending on the terrain: flatter sections where the water flows slowly needed to be larger. The depth of the aqueduct also varied: it's buried several metres below the surface in the bog just west of Shoal Lake, but exists as a mound right below the surface in most other sections.

All that digging amounted to a massive excavation job. Historical photos suggest the work was conducted by hand, horsepower as well as what appear to be hydraulic backhoes.

Hectares of forest along the route were harvested and several small towns - Ostenfeld, Ross, Hadashville, McMunn and East Braintree among them - sprang up along the way.

The project also saw workers build a causeway across Indian Bay to wall off the west side and divert the peaty water from Falcon Creek - which is safe but brown from tannins - into more distant Snowshoe Bay.

When the aqueduct opened in 1919, the cost of the project had ballooned to $17 million. That's roughly equal to $210 million in 2009 dollars, based on consumer-price inflation.

But today, the actual cost of this project this size would be much higher - perhaps more than $1 billion - due to disproportionate increases in the cost of both labour and construction materials over the past 90 years.

The city began adding chlorine to water at the intake site in the 1950s, but had no need to add new steps to the water-treatment process until this decade.

In 2006, water-treatment engineers at the Deacon Reservoir flipped the switch on a new ultraviolet-radiation facility that inactivates cryptosporidium, a nasty micro-organism that can't be killed off by chlorine treatment alone.

Later this year, a state-of-the-art, $300 million water-treatment plant will go online at the same site. It will improve the taste and smell of our water and use new treatment processes that will reduce the need for chlorination, a process that produces byproducts called trihalomethanes, which have been linked to a variety of diseases.

But for the next few months, water treatment remains a remarkably simple process, another testament to the wisdom of choosing Shoal Lake as a source.

After flowing past the fingers, which were built to slow wave action, our water passes below a headwall facing the lake. A boom extends along the front of the fingers to dissuade pickerel, which are attracted to moving water, from swimming toward the headwall.

But fish can't swim into the aqueduct, as a pair of screens - a stationary filter for large objects such as sticks and reeds, plus a rotating, fine-mesh screen to capture fish eggs and insects - prevents solid objects from entering the big pipe.

Even at this early stage in the flow, Winnipeg's water looks pristine. Inside the aqueduct intake building, a concrete-and-steel bunker built into a dynamite-blasted cavity in a granite ridge, the city's untreated water appears to be as translucent as artesian well water.

From here, the water flows into the aqueduct itself, where it then gets treated with chlorine. The chemical is added early on to allow it time to kill giardia, another lake-borne micro-organism.

The use of chlorine at this stage may be reduced or even eliminated after the Deacon water-treatment plant goes online, says Diane Sacher, Winnipeg's water services manager. But for now, it exists in our water along the entire 156-kilometre journey from Indian Bay, which takes about 30 hours.

Under normal conditions, gravity carries the water along the entire route. But if water levels on Indian Bay plummet, intake operators can switch on pumps to give the aqueduct flow the extra lift it needs to flow all the way to Winnipeg.

The last time the pumps had to be used was during the early-summer heat wave of 1988. Intake operators who had never had to use the pumps were forced to scramble their way through manuals, intake foreman Willis says.

Now, the city has procedures in place to deal with the prospect of another heat wave. But water use in Winnipeg has actually plummeted since the late '80s, thanks to conservation and the popularity of low-flow toilets and energy-efficient dishwashers.

During the June 1988 heat wave, which saw schools close at noon and water-use soar, the city almost issued an order for people to stop watering their lawns. At the time, daily water use peaked around 500 litres per person. But it's now only 326 litres per person, per day, Sacher says.

That has led Winnipeg to shelve plans to find a new water source to amend the existing aqueduct. Although Winnipeggers could certainly find ways to conserve more water, our collective behaviour has already changed, Sacher says.

"People will let their lawns go dormant if it doesn't rain," she says. "That didn't use to be the case."

Amazingly, the water and waste department actually shuts the aqueduct down for as long as a week at a time every year for routine maintenance. That's possible because the Deacon Reservoir can hold a 28-day supply of water - about 8.4 billion litres - inside its four cells just east of the Red River Floodway.

"It can act like a submarine in boggy sections," Sacher says. Indeed, entire kilometres of aqueduct are covered with crushed granite, which act as ballast in wetter areas.

While major aqueduct maintenance jobs are usually conducted once a year by a team of 10 city workers, the entire pipe is actually monitored constantly by a combination of human eyes and electronic sensors.

Throughout the length of the aqueduct, sensors placed inside and outside the pipe convey information about water flow, pressure and even vandalism to the aqueduct intake station. Remote sections of aqueduct are serviced by solar-powered monitoring stations.

Aqueduct workers also conduct visual inspections of every centimetre of the route no less than a twice a week. This work would be impossible without the city-owned G.W.W.D. Railway, which is traversed by converted GMC vans as well as conventional railcars.

The railway is also used to haul in heavy equipment such as excavators, which are used to destroy beaver dams near the aqueduct or cut new drainage channels in the bog.

While the pipe can handle pressure from above, it's vulnerable to uneven loads of water pressure that result from beaver activity on one side. It's also vulnerable to the effects of spring or summer flooding, especially from the Boggy River, near East Braintree.

Aqueduct maintenance workers also clear brush or trees from the area around the pipe to prevent damage from roots. But they don't use any pesticides to control weeds, Sacher says.

"If there's a break, we just want to deal with the problem, not contamination," she says.

Maintenance to the railway itself is also a constant concern. The city employs two crews of four railway-maintenance workers out of stations at Ross and Hadashville.

Workers can spend weeks at a time at Indian Bay, as they have to hang around when they're on standby. There are usually three on the job during the winter and five in the summer, including seasonal workers who commute three kilometres by motorboat from Shoal Lake 40 First Nation.

The aqueduct crew seems small compared to the quarters at their disposal: The site includes a mostly empty dorm facility with a kitchen, recreation room and beds for up to two dozen.

Back when politicians and senior city officials used to hold retreats at Waugh, the dorm facility was run as a resort, on a break-even basis. But the retreats fell out of fashion and the resort operations were closed, Sacher said.

Workers at Indian Bay must love the wilderness and the solitude that goes with it, says Andrew Weremy, a water services engineer who administers the intake site from his office in Winnipeg.

"It's very quiet. It's very isolated. If you like going to restaurants, you're going to have some trouble," he says.

The site has Internet service and satellite TV, but no road access whatsoever. A railcar is required for trips to East Braintree, the nearest town.

There are also unique workplace hazards. One of the black bears that hangs around the site is a yearling with a brown face that appears to have no fear of people. A hand-scrawled message on an intake control station blackboard warns staff and visitors that the critter is prone to chasing people.

Still, water and waste department employees still compete for the right to work here.

"It's a very unique place and very important to the city," says Willis, the intake foreman for the past three years.

So in 1989, the city and province reached an agreement with Shoal Lake 40 First Nation that would see the Anishinabe community resist the temptation to develop cottages in exchange for sustainable development expertise as well as funds flowing from a $6 million trust fund.

"We don't want to stagnate their development," said Sacher, noting the city has no problem with the community extending its modest network of roads. Shoal Lake 40 also has a septic system that was built to the satisfaction of the city of Winnipeg.

But another community on Indian Bay - Iskatewizaagegan 39 First Nation, eight kilometres northeast of Waugh - is serviced by sewage lagoons. There are reports the band is in the midst of a dispute with Ottawa over the sewage-treatment funding and maintenance.

Right now, Iskatewizaagegan's waste water problems are placing the remote community at risk but not the city of Winnipeg, Sacher says. The lagoon is far enough from Waugh to be diluted by Indian Bay, though there is no risk of contamination right now, she said.

But in the event Indian Bay takes a turn for the worse for some reason, Winnipeg's new water-treatment plant will be able to handle any biological contamination threat, she added.

The state-of-the-art plant in the R.M. of Springfield will employ four new water-treatment processes once it's online next year. Odour-causing algae will be clumped together by coagulants, forced to the surface with tiny air bubbles and then skimmed off into settling ponds. Ozone will break down organic molecules into smaller, more easily destroyed chains. Carbon filters will strain out particles and a beneficial slime will gobble up bacteria.

These processes will be added to two existing measures - ultraviolet radiation treatment to inactivate the cryptosporidium and chlorination to kill single-celled animals like giardia.

The end result means Winnipeggers won't really be drinking Shoal Lake water when the plant goes online this fall. We'll be drinking a highly processed version, free of the lake's microscopic flora and fauna.

But the supply of water has remained unchanged for almost a century, thanks to the unusual decision to build a 156-kilometre link between the city and the Lake of the Woods watershed.

그리고 좀 더 자세히 알기 위하여 구글맵(http://maps.google.ca)에서 Shoal Lake 를 찾아봤습니다. Shoal Lake는 Ontario주 Lake of Woods 와 인접해 있는 호수로 한국분들도 많이 놀러가는 Falcon Lake 남쪽에 있더군요.

위니펙시 수도는 90년전에 위니펙시로부터 156 km 떨어진 Shoal Lake 에서 위니펙시까지 두개의 수로를 건설하여 시민들에게 수도물을 공급하면서 시작했습니다. 그것에 얽힌 얘기를 간단하게 요약을 합니다.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

20세기초에 위니펙은 캐나다 횡단철도를 따라 많은 사람들이 오면서 도시가 급격히 커지기 시작했습니다. 그리고 먹는 물을 공급하기 위하여 개인회사가 아시니보인강변에 펌프를 설치하고 물을 공급하기 시작했습니다. 그 당시 물은 무척 불결해서 50명중 한명은 장티푸스, 콜레라, 또는 물과 관련된 병으로 죽었다고 합니다. 이에 1906년에 위니펙시는 지하수 우물(artesian wells)로 부터 물을 공급하기 시작하였으나 수요에 공급이 크게 못미쳤다고 합니다.

그래서 시는 깨끗한 물을 공급할 대책을 의논하기 시작했고, 시북쪽에 큰 우물을 여러개 파서 물을 공급하는 안, 위니펙강(Winnipeg River)에서 물을 끌어 오는 안, Shoal Lake 에서 물을 끌고 오는 안 등 3개안이 경합을 벌였다고 합니다. 당시 미국의 수도 건설 자문을 맡은 Charles Schlicter 가 Shoal Lake 안이 1912년 당시 돈으로 수로를 건설하는데 $13.5 million 이 들 것이라는 발표가 난 후 엄청 시끄러웠다고 합니다. 1913년 Shoal Lake 부근에 살던 시위원 Thomas Deacon 이 지지하는 Shoal Lake 안으로 결정이 되었고, 그 해 Thomas Deacon 이 위니펙 시장으로 당선되었고, 그 다음 시장으로 Deacon 의 뒤를 이어 Richard Waugh 이 선출되었습니다.

Charles Schlicter 발표한 Shoal Lake 안 수로 건설비는 당시 세계에서 인구가 빠르게 증가하는 도시중 하나로 미래의 증가할 인구수까지 감안하여 작성된 것이었습니다. 그는 그 증가하는 인구에게 임시적인 방법이 아닌 지속적으로 물을 공급할 수 있는 수로 용량으로 계산한 것으로 그의 계산은 일부가 잘못된 것이었습니다. 왜냐하면 1912년을 기점으로 위니펙시 인구가 증가하지 않고 정체했기때문이었습니다. 하지만 결과적으로 위니펙시는 굉장한 상수도 시스템을 갖게 되었습니다.

위니펙시에서 Shoal Lake 까지는156Km 거리로 고저차가 92 m 에 이릅니다. 1912년부터 1915년까지 위니펙시 외곽에서 Shoal Lake 까지 건설물자와 노동자를 운반하기 위하여 먼저 1,200명의 지역 및 이민 노동자가 투입되어 철도(The Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway)를 건설했습니다. 그리고 그들은 철도길 옆에 콘크리트로 말발굽모양의 수로를 건설하는데 다시 투입이 되었습니다.

1919년 수로가 완공되었을 때, 총공사비는 $17 million 로 늘어나 있었습니다. 2009년까지 물가인상율을 감안하면 $210 million 에 달하는 금액입니다. 하지만 오늘날 이 정도 크기의 공사를 실제로 한다면, 지난 90년동안의 노동인금과 건설자재값의 상승을 감안하면 아마도 쉽게 $1 billion 는 넘을 것입니다.

사진설명 : Shoal Lake Aqueduct under construction c1917

출처 : Winnipeg Free Press

처음 Shoal Lake 안을 지지했던 시장 Thomas Deacon 의 이름은 위니펙시 동쪽에 있는 정수장 the Deacon Reservoir 의 이름으로 사용되었고, 다음 시장 Richard Waugh 는 Shoal Lake 부근 수로입구의 지명으로 사용되었습니다.

구글맵에서 찾아 본 Deacon Reservoir 정수장

한두사람의 선견지명에 의해 수많은 사람들이 혜택 받는 것을 보면 정말 지도자를 잘 뽑아야 한다는 것을 알 수가 있습니다. 90년전에 지은 두개의 수로가 위니펙의 약 70만명 시민에게 아직까지 깨끗한 물을 정상적으로 공급한다는 것이 놀랍습니다.

다음은 위니펙 프리 프레스에서 찍은 동영상입니다.

좀 더 자세한 역사를 알고 싶은 분들을 위하여 위니펙 프리 프레스(Winnipeg Free Press) 기사를 덧붙입니다. 참고하세요.

The best decision Winnipeg ever made

At the turn of the 20th Century, railway-boom Winnipeg was growing faster than its supply of water. Private enterprises like the Winnipeg Water Works Company took pumped water straight out of the muddy Assiniboine River, which was increasingly polluted by human and farm animal waste, according to historian George Siamandas.Our drinking water was so filthy, as many as one in 50 Winnipeggers died of typhoid, cholera and other water-borne diseases, making the Manitoba capital one of the least safe cities on the planet to take a swig.

In 1906, the city started pumping water out of artesian wells. But the supply was too small to put out major fires.

So the city began to mull its options for a permanent and plentiful source of clean drinking water. City councillors wound up with three contenders: A larger series of wells north of the city, the Winnipeg River and Shoal Lake.

The debate over the choice was boisterous and divisive, especially after an American water consultant named Charles Schlicter pegged the price of the Shoal Lake option at $13.5 million, in 1912 dollars.

Schlicter based his decision on the fact Winnipeg was one of the fastest growing cities in the world at the time. Based on future population projections, it would need a substantial water supply.

"Winnipeg has entered into a class of world cities. It cannot afford to be committed to a temporary solution and it should not postpone the inevitable," wrote Schlicter, according to Siamandas.

Then-councillor Thomas Deacon, who had lived near Shoal Lake, pushed for the Indian Bay option. He won the decision in 1913 and was elected mayor later that year, succeeding Richard Waugh.

As it turned out, Schlicter was partly wrong: Winnipeg's runaway growth halted in 1912. But the decision to build the aqueduct was fortuitous in the sense it has wildly exceeded its expectation, in terms of both capacity and longevity.

Deacon is now immortalized by the Deacon Reservoir just east of Winnipeg. Waugh received the secondary honour of lending his name to the unincorporated community at the intake site.

Building through bog and boreal forest

On paper, the Winnipeg Aqueduct was a simple device: Gravity carries water from Shoal Lake to Winnipeg, a vertical drop of 92 metres spread out over 156 kilometres.But before construction could begin, the city had to build a railway all the way to the intake site to transport all the manpower, machinery and materials to build the aqueduct. Concrete and steel could not be schlepped on foot or horseback over the prairie, forest and bog that separated Winnipeg from Indian Bay.

The Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway was laid down between 1913 and 1915 by 1,200 local and migrant workers. They then went to work on the task of building the aqueduct itself, which features a flat bottom of steel-reinforced concrete with a horseshoe-shaped concrete arch over top, which derives its strength from its own weight.

Every mile along the aqueduct, the top of the arch was reinforced with steel to allow for future road crossings. Rural Manitoba has a network of roads spaced one mile apart, and the designers wanted to make sure motor vehicles would not destroy the aqueduct.

The circumference of the aqueduct varied, depending on the terrain: flatter sections where the water flows slowly needed to be larger. The depth of the aqueduct also varied: it's buried several metres below the surface in the bog just west of Shoal Lake, but exists as a mound right below the surface in most other sections.

All that digging amounted to a massive excavation job. Historical photos suggest the work was conducted by hand, horsepower as well as what appear to be hydraulic backhoes.

Hectares of forest along the route were harvested and several small towns - Ostenfeld, Ross, Hadashville, McMunn and East Braintree among them - sprang up along the way.

The project also saw workers build a causeway across Indian Bay to wall off the west side and divert the peaty water from Falcon Creek - which is safe but brown from tannins - into more distant Snowshoe Bay.

When the aqueduct opened in 1919, the cost of the project had ballooned to $17 million. That's roughly equal to $210 million in 2009 dollars, based on consumer-price inflation.

But today, the actual cost of this project this size would be much higher - perhaps more than $1 billion - due to disproportionate increases in the cost of both labour and construction materials over the past 90 years.

How the water flows

When Winnipeg's aqueduct opened, Shoal Lake water was so pristine that it did not require any treatment, given the standards of the day.The city began adding chlorine to water at the intake site in the 1950s, but had no need to add new steps to the water-treatment process until this decade.

In 2006, water-treatment engineers at the Deacon Reservoir flipped the switch on a new ultraviolet-radiation facility that inactivates cryptosporidium, a nasty micro-organism that can't be killed off by chlorine treatment alone.

Later this year, a state-of-the-art, $300 million water-treatment plant will go online at the same site. It will improve the taste and smell of our water and use new treatment processes that will reduce the need for chlorination, a process that produces byproducts called trihalomethanes, which have been linked to a variety of diseases.

But for the next few months, water treatment remains a remarkably simple process, another testament to the wisdom of choosing Shoal Lake as a source.

After flowing past the fingers, which were built to slow wave action, our water passes below a headwall facing the lake. A boom extends along the front of the fingers to dissuade pickerel, which are attracted to moving water, from swimming toward the headwall.

But fish can't swim into the aqueduct, as a pair of screens - a stationary filter for large objects such as sticks and reeds, plus a rotating, fine-mesh screen to capture fish eggs and insects - prevents solid objects from entering the big pipe.

Even at this early stage in the flow, Winnipeg's water looks pristine. Inside the aqueduct intake building, a concrete-and-steel bunker built into a dynamite-blasted cavity in a granite ridge, the city's untreated water appears to be as translucent as artesian well water.

From here, the water flows into the aqueduct itself, where it then gets treated with chlorine. The chemical is added early on to allow it time to kill giardia, another lake-borne micro-organism.

The use of chlorine at this stage may be reduced or even eliminated after the Deacon water-treatment plant goes online, says Diane Sacher, Winnipeg's water services manager. But for now, it exists in our water along the entire 156-kilometre journey from Indian Bay, which takes about 30 hours.

Under normal conditions, gravity carries the water along the entire route. But if water levels on Indian Bay plummet, intake operators can switch on pumps to give the aqueduct flow the extra lift it needs to flow all the way to Winnipeg.

The last time the pumps had to be used was during the early-summer heat wave of 1988. Intake operators who had never had to use the pumps were forced to scramble their way through manuals, intake foreman Willis says.

Now, the city has procedures in place to deal with the prospect of another heat wave. But water use in Winnipeg has actually plummeted since the late '80s, thanks to conservation and the popularity of low-flow toilets and energy-efficient dishwashers.

How much water is enough?

When the aqueduct was completed, it had a capacity to carry 387 million litres of water a day. Today, it only carries an average of 225 million litres, as water use in Winnipeg has levelled.During the June 1988 heat wave, which saw schools close at noon and water-use soar, the city almost issued an order for people to stop watering their lawns. At the time, daily water use peaked around 500 litres per person. But it's now only 326 litres per person, per day, Sacher says.

That has led Winnipeg to shelve plans to find a new water source to amend the existing aqueduct. Although Winnipeggers could certainly find ways to conserve more water, our collective behaviour has already changed, Sacher says.

"People will let their lawns go dormant if it doesn't rain," she says. "That didn't use to be the case."

Amazingly, the water and waste department actually shuts the aqueduct down for as long as a week at a time every year for routine maintenance. That's possible because the Deacon Reservoir can hold a 28-day supply of water - about 8.4 billion litres - inside its four cells just east of the Red River Floodway.

Keeping the aqueduct ducky

Historically, aqueduct inspectors who wanted to take a peek at the interior of the big pipe used boats or even rode specially tricked-out bicycles. Today, inflatable dams are placed inside sections of the aqueduct and then filled with water to prevent the structure from floating while it's empty."It can act like a submarine in boggy sections," Sacher says. Indeed, entire kilometres of aqueduct are covered with crushed granite, which act as ballast in wetter areas.

While major aqueduct maintenance jobs are usually conducted once a year by a team of 10 city workers, the entire pipe is actually monitored constantly by a combination of human eyes and electronic sensors.

Throughout the length of the aqueduct, sensors placed inside and outside the pipe convey information about water flow, pressure and even vandalism to the aqueduct intake station. Remote sections of aqueduct are serviced by solar-powered monitoring stations.

Aqueduct workers also conduct visual inspections of every centimetre of the route no less than a twice a week. This work would be impossible without the city-owned G.W.W.D. Railway, which is traversed by converted GMC vans as well as conventional railcars.

The railway is also used to haul in heavy equipment such as excavators, which are used to destroy beaver dams near the aqueduct or cut new drainage channels in the bog.

While the pipe can handle pressure from above, it's vulnerable to uneven loads of water pressure that result from beaver activity on one side. It's also vulnerable to the effects of spring or summer flooding, especially from the Boggy River, near East Braintree.

Aqueduct maintenance workers also clear brush or trees from the area around the pipe to prevent damage from roots. But they don't use any pesticides to control weeds, Sacher says.

"If there's a break, we just want to deal with the problem, not contamination," she says.

Maintenance to the railway itself is also a constant concern. The city employs two crews of four railway-maintenance workers out of stations at Ross and Hadashville.

City workers, remote location

Throughout the year, three to five people work out of the aqueduct intake station at Waugh, easily the most remote and unusual jobsite run by the city of Winnipeg.Workers can spend weeks at a time at Indian Bay, as they have to hang around when they're on standby. There are usually three on the job during the winter and five in the summer, including seasonal workers who commute three kilometres by motorboat from Shoal Lake 40 First Nation.

The aqueduct crew seems small compared to the quarters at their disposal: The site includes a mostly empty dorm facility with a kitchen, recreation room and beds for up to two dozen.

Back when politicians and senior city officials used to hold retreats at Waugh, the dorm facility was run as a resort, on a break-even basis. But the retreats fell out of fashion and the resort operations were closed, Sacher said.

Workers at Indian Bay must love the wilderness and the solitude that goes with it, says Andrew Weremy, a water services engineer who administers the intake site from his office in Winnipeg.

"It's very quiet. It's very isolated. If you like going to restaurants, you're going to have some trouble," he says.

The site has Internet service and satellite TV, but no road access whatsoever. A railcar is required for trips to East Braintree, the nearest town.

There are also unique workplace hazards. One of the black bears that hangs around the site is a yearling with a brown face that appears to have no fear of people. A hand-scrawled message on an intake control station blackboard warns staff and visitors that the critter is prone to chasing people.

Still, water and waste department employees still compete for the right to work here.

"It's a very unique place and very important to the city," says Willis, the intake foreman for the past three years.

Concerns for the future

In the 1980s, when more Winnipeggers began building cottages in and around Shoal Lake, there were concerns about the future quality of Indian Bay water. City officials feared cottage activity could lead to nutrient loading and the presence of more algae in the lake water.So in 1989, the city and province reached an agreement with Shoal Lake 40 First Nation that would see the Anishinabe community resist the temptation to develop cottages in exchange for sustainable development expertise as well as funds flowing from a $6 million trust fund.

"We don't want to stagnate their development," said Sacher, noting the city has no problem with the community extending its modest network of roads. Shoal Lake 40 also has a septic system that was built to the satisfaction of the city of Winnipeg.

But another community on Indian Bay - Iskatewizaagegan 39 First Nation, eight kilometres northeast of Waugh - is serviced by sewage lagoons. There are reports the band is in the midst of a dispute with Ottawa over the sewage-treatment funding and maintenance.

Right now, Iskatewizaagegan's waste water problems are placing the remote community at risk but not the city of Winnipeg, Sacher says. The lagoon is far enough from Waugh to be diluted by Indian Bay, though there is no risk of contamination right now, she said.

But in the event Indian Bay takes a turn for the worse for some reason, Winnipeg's new water-treatment plant will be able to handle any biological contamination threat, she added.

The state-of-the-art plant in the R.M. of Springfield will employ four new water-treatment processes once it's online next year. Odour-causing algae will be clumped together by coagulants, forced to the surface with tiny air bubbles and then skimmed off into settling ponds. Ozone will break down organic molecules into smaller, more easily destroyed chains. Carbon filters will strain out particles and a beneficial slime will gobble up bacteria.

These processes will be added to two existing measures - ultraviolet radiation treatment to inactivate the cryptosporidium and chlorination to kill single-celled animals like giardia.

The end result means Winnipeggers won't really be drinking Shoal Lake water when the plant goes online this fall. We'll be drinking a highly processed version, free of the lake's microscopic flora and fauna.

But the supply of water has remained unchanged for almost a century, thanks to the unusual decision to build a 156-kilometre link between the city and the Lake of the Woods watershed.

관련자료

댓글 0

등록된 댓글이 없습니다.